Beyond the Milk Run: What Grocery Stores Know About Space That Your Business Does Not

Every retail professional knows the cliché: milk goes in the back of the store to force impulse purchases. But if you think that’s just a trick to sell more candy bars, you’re missing the bigger story—one that could transform how you think about every square foot of space you manage.

The placement of milk isn’t arbitrary manipulation. It’s the intersection of hard logistics and sophisticated behavioral design. And the principles behind it apply whether you’re running a regional mall, planning a trade show floor, or optimizing a franchise footprint.

The Real Reason Milk Lives in the Back

Yes, putting milk at the back forces customers to walk past tempting items. But there’s something else at play: milk needs to be there.

Refrigeration units are energy-intensive. They work best against exterior walls near loading docks, minimizing the distance heavy pallets must travel. The psychology follows the logistics, not the other way around.

This is the first lesson for modern retail space management: constraints can become advantages. The question isn’t “how do we trick people?” It’s “given our operational realities, how do we design a system that creates value for both the business and the customer?”

Two Revolutions That Built Modern Retail

Understanding where we are requires knowing where we came from.

The Piggly Wiggly Revolution (1916)

Before Clarence Saunders opened his Piggly Wiggly store in Memphis, shopping meant handing a list to a clerk. Saunders invented something radical: the self-service store with a continuous path layout that forced customers past every single item before reaching checkout.

His insight was elegant: if customers don’t see it, they can’t want it. This principle evolved into the IKEA maze, where the path itself becomes the product, ensuring complete inventory exposure.

The Gruen Effect (1950s)

Austrian architect Victor Gruen designed the first enclosed American shopping mall to be a “third place” for suburban communities. But retailers discovered something unexpected: his aesthetically pleasing, slightly disorienting layouts caused customers to lose track of time and become more susceptible to impulse purchases.

Gruen’s principle of “inward-facing” retail—where the world inside matters more than the world outside—remains the foundation of modern mall design.

The Dual Force Model: Logistics + Psychology

The most sophisticated retail strategies recognize two forces at work:

Hard Constraints (Logistics): These are non-negotiable operational realities. In grocery stores, refrigeration dictates placement. In malls, anchor tenants need massive square footage and loading access, forcing them to the perimeter. In trade shows, electrical infrastructure and weight capacity determine where certain exhibitors can go.

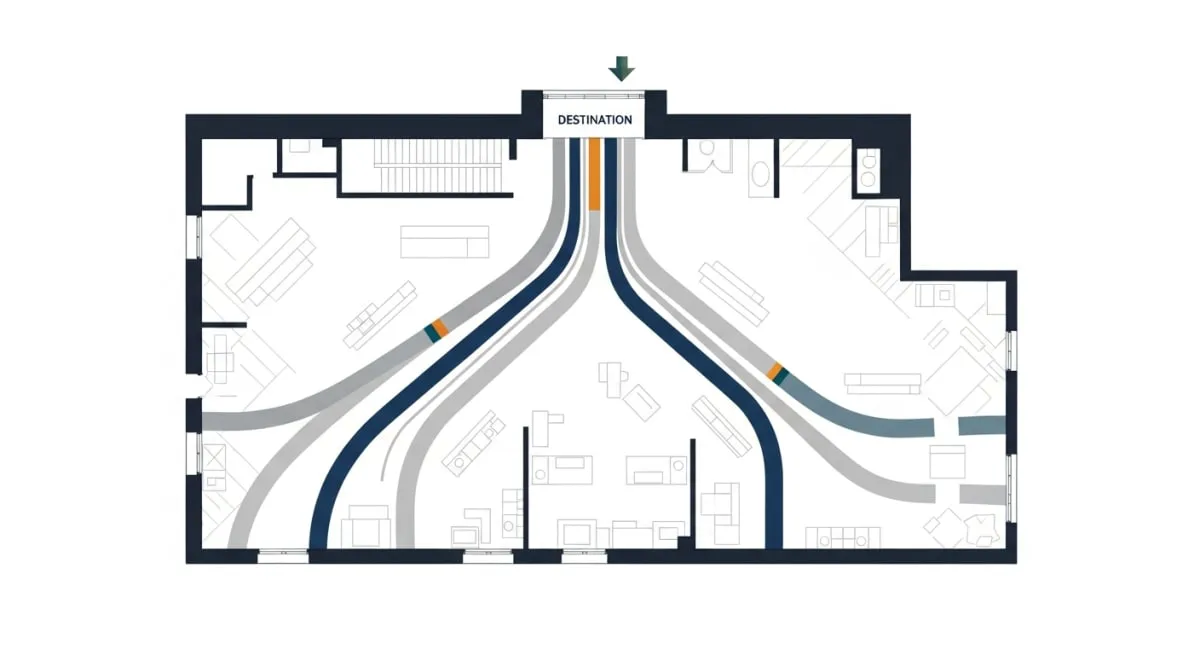

Soft Constraints (Psychology): These are behavioral patterns you can shape. Destination items create search patterns. Anchor tenants at opposite ends force traffic through corridors. Strategic dead ends become discovery zones.

The magic happens when you design systems where logistics and psychology reinforce each other rather than fight.

Translating Principles Across Retail Environments

For Shopping Centers: The Vertical Waterfall

Grocery stores use back walls to pull customers deep. Multi-level retail spaces must pull customers up.

Place your food court or cinema on the top floor. This creates a “gravity effect”—customers travel upward for a destination, then trickle down past retail tenants on their exit. Upper-level tenants who typically pay lower rent suddenly receive anchor-driven foot traffic.

Your restrooms and ATMs? Never put them near entrances. A customer seeking a restroom has high intent; they will walk past twenty storefronts to find it. Use this to activate dead zones and validate otherwise challenging lease space.

For Trade Shows: The Decompression Zone

Grocery stores never place high-value items immediately inside the door because customers are moving too fast to notice them. The first fifteen to thirty feet is a “no-sell zone” where people are transitioning, orienting, adjusting to the environment.

At trade shows, this means your premier exhibitors shouldn’t be in the first row. Place them where attendees have settled into the space and their peripheral vision has opened up. Use that entrance zone for registration, wide transition areas, and wayfinding—not revenue generation.

For Franchises: The Endowment Effect

In grocery psychology, a shopper who places one item in their basket is 75% more likely to buy a second item. They’ve mentally endowed themselves with the role of buyer.

For franchises, this means creating “micro-wins” early in the customer journey. A low-commitment purchase—a coffee, a sample, a small add-on—breaks the browsing barrier and transforms someone from a looker into a buyer.

The strategic question: what’s your equivalent of putting that first item in the basket?

The Data Revolution: From Intuition to Evidence

Modern retail has moved beyond gut feel to data-driven optimization.

Heat mapping technology using Wi-Fi tracking and camera analytics now reveals exactly where people stop, linger, and buy. If a corridor has high traffic but low conversion, you have a “pass-through” zone—a failure of tenant mix, not foot traffic.

The insight isn’t just about identifying hot zones. It’s about diagnosing why certain areas underperform and making surgical corrections. A bank branch in a pass-through zone is wasted opportunity. A sneaker store there captures momentum.

The Modern Question: Are You Managing Space or Designing Behavior?

The milk at the back isn’t a trick. It’s a system. And systems thinking is what separates tactical retail management from strategic leadership.

The questions for your organization:

- What are your “milk” items—the destinations so valuable that customers will traverse your entire space to reach them?

- Where are your hidden constraints—the operational realities that, if acknowledged and designed around, could become strategic advantages?

- What does your data reveal about where people stop versus where they merely pass through?

- Are you wasting prime real estate in decompression zones where customers are psychologically unavailable?

Most importantly: Are you designing for the customer journey you want, or just accepting the one that emerged?

Given where people need to go and what we need them to see, how do we design the path?

The answer might not involve milk. But the thinking certainly should.